- Home

- Wayne Shorey

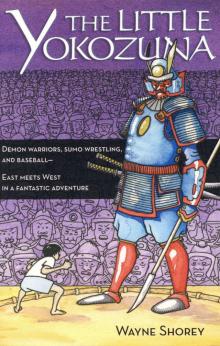

Little Yokozuna Page 9

Little Yokozuna Read online

Page 9

"Right," said Annie. "Owen, do you know those names?"

"Of course," said Owen Greatheart. "Yazu must be Yaz. Carl Yastrzemski, that is. And then obviously Tony Conigliaro and Rico Petrocelli. What was the other one again?" Kiyoshi-chan repeated it. "Naturally," said Owen Greatheart. "Jim Lonborg, twenty-two wins that season. How do you know so much about the '67 Red Sox, Kiyoshi-chan? My dad was a kid then. A little before your time."

Kiyoshi-chan looked completely flummoxed. None of this made any sense at all. It made him wonder again whether the American children had learned some strange dialect of Japanese that they switched into occasionally, by accident.

"No," said Annie quietly. "They're not before his time at all."

All the siblings looked at their oldest sister.

Owen Greatheart scratched his head. "OK," he said. "I give up. Explain, Annie."

"It's no riddle," said Annie. "It's just that the gardens do more than transport us across space."

Owen Greatheart squinted at her, with a somewhat sick expression.

"No," he said.

"Yes," said Annie.

"Do you mean time, Granny?" said Knuckleball excitedly. "Cool!"

"Not so cool," said Annie. "We're in 1968, Knuckles."

"So?" said Knuckleball. "That's what's so cool."

"Think, O brainless one," said Annie. "The coolness of it disappears when you realize what it means. How can any of us take a plane back to Boston? Mom and Dad won't even be there for years yet! We're lost in time, Peach Boy, with no way home."

Knuckleball, 'Siah, and Libby took this in with wide eyes, suddenly realizing the implications. The thought of that friendly airplane that seemed all ready to take them home whenever they really wanted it, had for a long time been an unspoken comfort to them all. Their faces began to crumble into despair. Annie got down on her knees quickly and wrapped them in her long arms.

"But there's still hope," she said. "It's only airplanes and trains and boats that can't take us across time. Do you know what that means?"

The little children shook their heads, slowly.

"It means we're all doing the Garden," said Annie brightly. "Together."

CHAPTER 14

The Garden of a Thousand Worlds

The Garden opened to receive the six American children and Basho the monkey, who had insisted on coming along. They said good-bye to their Japanese friends, thanking them for all of their help. But as Kiyoshi-chan and Knuckleball bowed their sad farewells to each other, there seemed to be a lively consultation still going on among the adults of the family. In fact, the old obaa-san seemed actually to be arguing, showing more animation than the American children had ever seen in her. When the children made it clear that they were going at last into the Garden, Kiyoshi-chan's parents were polite but distracted in their good-byes, as if something was still unsettled.

This distant sort of farewell was disappointing, but before they had even gotten beyond the mossy mound that had been their deepest penetration into the Garden earlier, the gate banged behind them and Kiyoshi-chan came bursting through.

"Kiyoshi-chan!" cried Knuckleball. "What are you doing in here?"

"I'm coming with you," said Kiyoshi-chan, flushed with excitement.

"How did that happen?"

"My grandmother said I had to," said Kiyoshi-chan, incredulously. "That I might be needed. My mother said No. My father said that it's only another garden, and that we would all be coming out again almost as quickly as we went in, so why not? My mother said that it's not only a garden. My grandmother said that she was right and my father was wrong, it's not only a garden, but that I would be all right. My grandfather didn't say anything. I think all four of them thought each other was crazy. Finally they just said Go. So here I am!"

This all came out in a breathless rush, so that when Kiyoshi-chan finished he had to stop and recover. Knuckleball laughed. "It can't get any better than this!" he said, clapping Kiyoshi-chan on the back.

"Except for finding Little Harriet," said Q.J. "That would be better."

"I know that, Quid," said Knuckleball, annoyed that she would have thought he might have forgotten it.

"No fighting," said Annie. "Let's go."

They went around the bend at last, the one they had been able to see from their first entrance into the Garden. The path was made of smooth dark river rocks, so glossy that it seemed they should have been slippery but weren't. Dark green moss grew between the flat stones, which were spaced at irregular but comfortable intervals along the path. The children were hushed as they came out of the little curve and found themselves in a long straightaway, thickly hedged on both sides and overhung with maples.

"Hm," said Owen Greatheart. "I wouldn't have thought this was here, from what I saw up on the mound. I would have expected more of a twisty sort of path right here. But I guess I couldn't really see it too clearly."

There was nothing to say to this. They walked slowly down the pathway, stepping from one smooth dark stone to the next. There were birds in the trees overhead, but because of the thickness of the foliage they were invisible. The Garden seemed a sleepy, trance-like place, for the moment.

"Doesn't it feel like we're going downhill?" asked Q.J. "But the path looks perfectly level."

It was true. Something gave the distinct impression that they were descending deeper into a valley, but their eyes told them clearly otherwise.

"Odd," said Owen Greatheart.

The green shadowiness of the pathway deepened as they went along it, the foliage overhead thickening and the bordering hedges drawing in, narrowing. The end of the straightaway was in sight, but was in such deep shadow that it wasn't until they had almost reached it that they realized it was a thick stand of black bamboo, dripping with rain. The path of glossy stepping-stones meandered sharply to the left through the bamboo, just wide enough for single file. They entered the grove with Basho in the lead.

"That rain came on us in a hurry," said Annie, squinting up at the overcast sky. "I sure thought it was a clear enough day outside the Garden."

"It's just a drizzle," said Owen Greatheart, but it was enough of a drizzle for the spear-shaped bamboo leaves above to trickle steadily onto their heads until they were soaked. The overcast grove was in deep emerald shade, its ground covered with tall streaming ferns. The ferns themselves seemed to glow with a soft green light of their own against the black stems of the bamboo.

"This just might be the most beautiful place I have ever seen," said Q.J.

"Yes," said Owen Greatheart.

They finally came out of the bamboo into mottled sunlight, and onto an earthen trail that wound steeply upward.

"Well!" said Annie. "Fickle weather."

The trail plunged ahead into a great crowd of boulders, some of them towering twenty feet into the air. The path itself, making its way between the boulders, became a rough stone staircase that looked from below like a rushing torrent, a river frozen into weathered stone.

"Up we go," said Knuckleball. "Looks like we're in for a mountain climb."

"Looks like it," said Q.J.

But despite its steepness, the natural steps of the Tocky staircase were at easy intervals, and they went up it quickly, toward a thick stand of wild pines. There was an evergreen wind all around them as they came to the top of the stone staircase and found themselves overlooking still another, entirely new landscape.

"This can't all fit in here," said Owen Greatheart.

This, once again, had no answer. In front of them was a steep bank, down which they could look on the top of a stone lantern and a small pagoda, almost as if they were on a mountaintop looking down on human habitations of the world. The path bent quickly off to the right, making its way down a dwindling ridge until it let them off on the smooth stone shore of a large pond. They could see all around the pond, which as Owen Greatheart pointed out, should not all by itself have fit into the actual acreage of the Garden. At their feet was a beach of smooth round stones, but to th

eir left the pond was edged by massive rock formations sprinkled with maple leaves. The air here was cool, almost October-like.

"Why a bridge to nowhere?" asked Annie. A roughcut stone arch reached out into the pond from the beach they stood on, and rested its other end on a large lichened boulder perhaps fifteen feet from shore.

"Not to nowhere," said Kiyoshi-chan. "To there."

So they stepped up on the bridge and walked out to its end, where so many bright orange carp came to meet them that the water seemed to boil with fish.

"Wow," said 'Siah.

They looked all around and saw the pond area from a new angle, as if it were a new pond. It was ringed with autumn trees of all kinds, and yellow and red leaves drifted down and floated on the surface of the pool.

"Is it still April?" wondered Q.J.

"Who knows? Let's go on," said Annie.

"Just what are we looking for?" asked Owen Greatheart. "Do we have any idea?"

"I don't," said Annie. "Do you?"

Returning to the path they went on, every turn bringing a new revelation, an unexpected landscape under an ever-new season and kind of daylight. Under a bright noonday sun, there was a simple shadowless expanse of rippled white gravel, heaped here and there with mysterious cones of silver sand. There was an early morning hillside of dewy junipers, sculpted into unearthly, fantastic forms and gleaming with the dawn light as if bejeweled. Under a slate December sky there was a miniature black pine in a wooden box, surprisingly dusted with light snow. There were riots here and there of camellias, azaleas, rhododendrons, chrysanthemums. There was a painted, windswept pavilion overlooking a wildly overgrown pool, backlit by a sad westering sun. There was a morning grove of weeping cherry trees, trailing fragile blossomed streamers in the spring breeze.

It was all heartbreaking, exquisite, evanescent, like Life itself.

"This is too much," said Owen Greatheart, almost resentfully. "This is much too much."

They came to a low bamboo gate and opened it, finding a small secretive garden space. There was a streambed of multicolored round pebbles, covered by a shallow, unrippled run of clear water. Larger stones, low dark green red-berried bushes, giant ferns, clustered hemlocks, and one squat goose-like stone lantern crowded the little stream, creating spaces of ambiguous reflection and meditative shadow. The shrouded stream drew the children's eyes in, up its jumbled mossy bank to the dark delphic grove from which it fell.

"Just look at this," said Annie, flinging herself down on the ground. "The trouble with this is not that it's just beautiful. Beauty I can handle."

"I know what you mean," said Owen Greatheart.

"I don't," said Knuckleball. "Explain."

"Well," said Annie, "it's the way that all of this has of looking like it's so significant. As if it's all hiding something that we're supposed to know."

"Exactly," said Q.J. "Every new landscape I see here, something in me says Yes! That's what I've been looking for all my life! But then I still can't figure out what it is I was looking for all my life, even though it seems to be right in front of me."

"Little Harriet," said Libby. "That's what we're looking for."

"Well, of course," said Annie. "But I know just what Q means. It's like a poem that means more than its words say, but you can't figure out the meaning no matter how hard you try."

"It frustrates me," said Owen Greatheart. "I feel like there's something wrong with my eyes, as if I'm seeing things but not really seeing them."

"Just the surface of them," said Q.J. "It almost makes you want to see something that's just plain pretty in a simpleminded sort of way."

"Is there really any such thing?" wondered Annie. "I don't know if I'll ever be able to see something as simply pretty again. I'll always be wondering what I'm missing."

"I wouldn't have missed seeing the Garden," said Owen Greatheart. "Don't get me wrong. But I do wonder if it might not be spoiling us for real life."F

"I don't think so," said Q.J.

"You know," said Annie, "you get the feeling that if you could only hit on the key to this Garden, everything in the Universe would make sense."

"Kind of like all the answers to everything are hidden here," said Q.J.

"No!" said Annie. "Kind of like all the questions are hidden here. I don't think I even know the right things to ask yet."

"Seems to me," said Owen Greatheart, "that if we stayed here for a thousand years, we might finally learn the right questions."

"Then we could start on the answers," said Libby.

"We'd be pretty old by then," said Knuckleball.

No one spoke for a moment, listening to the whisper of the stream.

"Well, I have a question," said 'Siah, loudly. "Where is the bathroom?"

"Oh, my," groaned Owen Greatheart.

"Pick a tree," said Q.J. "Any tree."

"Do you think the Garden will mind?" asked Owen Greatheart, taking 'Siah by the hand and leading him out of sight. The other children lay quietly on their backs, watching the tree branches waving far above them, until the two boys returned.

"Well," said Libby, "Now / have a question."

"Nearest tree, Squib," said Q.J. "You're a big girl. You're on your own."

"Not that," said Libby. "I just want to know how all this is helping us find Little Harriet."

"I don't know," said Annie. "For that, I think we're just at the whim of the Garden. All we can do is wander, and wait, and poke around."

"How about if we chase a chipmunk?" suggested Libby. "Just like Little Harriet did, back in Boston? Maybe chipmunks are some kind of guides to the garden gateways."

"Great idea, Squibbles," said Q.J. "We'll wait here. You go chase a chipmunk."So she lit off after a striped little fellow that was sit ting on an old gray boulder, and as if pulled after her by a cord, all the children leaped up laughing and went along with the whimsy, following the tiny beast on a mad and merry chase, round and round, in and out. And who knows whether what followed was the simple caprice of the Garden, something special about that little chipmunk, or something else altogether? The fact is that when they finally clambered after the nimble creature up the stream and up the mossy bank and over the top into a soft pungent tumble of fern and evergreen needles and autumn leaves, they suddenly felt the ground dissolving away under them so that they gasped and caught each other's hands.

"Here we go!" cried 'Siah, and the Garden came rushing out and over them like an irresistible flood, a green and gold and silver tsunami of beauty and undiscovered mystery, sweeping them far, far, far away to another world where none of them had ever been before.

CHAPTER 15

The Arena

They stood at the joining of two long hallways, which ran away from them at right angles to each other. The hallways had floors of fine pale tatami mats, and high ceilings of simple polished wood. Each of the two hallways was at least as long as two football fields, and as wide as two mats, perhaps wide enough for four people to walk side by side. In the distance the children could see where the hallways seemed to corner again at sharp angles to run toward each other, as if they formed a huge square. The walls along the outside of this apparent square were of white plaster, interrupted at intervals by great polished, unpainted pillars set into the plaster, as big as trees. Light came from unreachable latticed windows near the ceiling, covered over with shoji, undecorated rice paper. The inside walls were entirely different, not walls at all, but sliding shoji doors running the whole length of the hallways.

There was no garden in sight, not even a potted plant. And there were no visible exits.

The first impression of the place was of utter vacancy and stillness. Only gradually did they become aware that there was a deep hushing sound all around them, like the voice of the ocean, or of a vast audience waiting for a performance to begin.

The children realized that they were still holding hands tightly, scarcely breathing. They exhaled all at once and looked at each other.

"Well," said Libby. "H

ere we are."

"This is a beautiful place," said Owen Greatheart. "Look at the ceilings. We can see ourselves in them."

"What do we do now?" asked Knuckleball. "Which way do we go? Looks like we have two choices."

"That's one more than we had down in the mine, right, Lib?" said Q.J. "I say let's go to the right."

"That's because you are American, and always go right," said Kiyoshi-chan. "You even drive on the right side of the road, and read from left to right."

"That's true," said Annie. "Somehow it does seem right to go left this time."

Everyone agreed, and set off down the hallway, with 'Siah and Basho having a somersault race to the first corner. But as it turned out, right or left made no difference, because when they had turned three sharp corners and walked four lengths of hallway, they ended up right back where they had begun. All four sides of the square hallway were identical, without exits or reachable windows.

"Hm," said Owen Greatheart, with a frown. "This is strange."

"Curiouser and curiouser," said Q.J., like Alice in Wonderland.

The ocean-like hum around them seemed to have grown a little louder, and in fact seemed to ebb and flow a bit, with individual sounds in it.

"I think that is a crowd," said Knuckleball. "It sounds like Symphony Hall just before the concert begins."

"Except there's no squeaky tuning going on," said Libby.

"I wonder if Knuckleball could reach that window if he stood on my shoulders," said Owen Greatheart. "He could poke a hole in the rice paper and tell us what's outside."

"You can't just go poking holes in somebody else's shoji!" said Annie.

"Why not?" said Owen Greatheart. "You want to just sit in here forever?"

"Of course not," said Annie. "But we're certainly not desperate enough yet to have to go poking holes in shoji"

"And besides," said 'Siah, "I don't think that noise is coming from outside. I think it's coming from there" He pointed toward the inner wall of sliding doors, which up till now they had ignored. The paper doors stared blankly past them, as if asking to be overlooked.

Little Yokozuna

Little Yokozuna