- Home

- Wayne Shorey

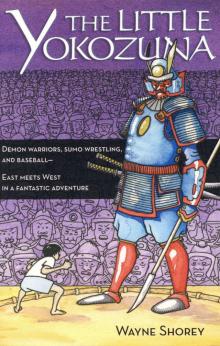

Little Yokozuna

Little Yokozuna Read online

First published in 2003 by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., with editorial offices at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759 U.S.A.

Copyright © 2003 Wayne Shorey

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from Tuttle Publishing.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

LCC Card Number: 2002075061

Shorey, Wayne.

The little Yokozuna / Wayne Shorey

1st ed.

Boston, Mass. : Tuttle Pub., 2003.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0741-0 (ebook)

Distributed by:

North America, Latin America,

and Europe

Tuttle Publishing Distribution Center

Airport Industrial Park

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436

Tel: (802) 773-8930

Fax: (802) 773-6993

Email:[email protected]

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280 1330

Fax: (65) 6280 6290

Email: [email protected]

Web site: www.periplus.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Bldg., 3F

5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku

Tokyo 141-0032

Tel: 81 (03) 5437-0171

Fax: 81 (03) 5437-0755

Email: [email protected]

First edition

08 07 06 05 04 03 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Serena Fox Design

Printed in Canada

CONTENTS

Chapter One Something Happens to Kiyoshi-chan

Chapter Two Night Sounds

Chapter Three Knuckleball Takes a Swing

Chapter Four A Little Hope for Little Harriet

Chapter Five Breaking and Entering

Chapter Six Owen Greatheart Explains Things

Chapter Seven Sumo Lessons

Chapter Eight The Way Out

Chapter Nine Weaving a Net of Words

Chapter Ten From Bad to Worse in the Dead End Mine

Chapter Eleven Annie and Knuckleball Almost Miss Kyoto

Chapter Twelve The Knock on the Gate

Chapter Thirteen One Way Home

Chapter Fourteen The Garden of a Thousand Worlds

Chapter Fifteen The Arena

Chapter Sixteen The Demon Warrior Makes Promises

Chapter Seventeen Finding a True Rikishi

Chapter Eighteen Kiyoshi-chan Does His Best

Chapter Nineteen Finding Little Harriet

Chapter Twenty Impossible Choices

Chapter Twenty-One Under the Deep Green Sea

Epilogue Epilogue

CHAPTER 1

Something Happens to

Kiyoshi-chan

There was once a young boy named Kiyoshi-chan, who was born in a village called Kashiwa, in the ancient country of Japan, and who then had nothing happen to him for the first eleven years of his life.

If this sort of thing had gone on, of course, there would be no story to tell about Kiyoshi-chan, since for a story to be a story something has to happen. But as it came about, there finally was a certain rainy night when everything seemed to start happening to Kiyoshi-chan at once, changing his life forever.

At the time of this adventure, Kiyoshi-chan would have said that he was eleven years old. The reason for this is that from olden times, when the Japanese count age they include the year of life inside the mother's womb, before the child is born. Kiyoshi-chan liked this custom. American children would have called him ten, which would have hurt Kiyoshi-chan's pride a bit, but there it is.

By the time he was eleven, then, Kiyoshi-chan had learned to love several things above all else. First, he loved the great sport of sumo with a grand passion. Six times a year he watched the Grand Sumo Tournaments on the little black-and-white TV his father kept in the quilt closet, and he could never stop talking about his favorite rikishi, or sumo wrestlers. He had actually attended several of the great tournaments in person, awed by the pageantry and by the presence of some of history's most famous wrestlers. "I am one of the luckiest Japanese boys ever," he said one day, when he was much younger. "Why is that?" his mother asked. "Because I live in the days of Taiho, the greatest yokozuna of all time," he said. "Think of all the boys in olden times who never heard of Taiho, or the boys in the future who will wish they had seen him. I am in just the right time of history."

And how many people can say that, believing it?

Next to sumo, Kiyoshi-chan loved baseball, and in a very different way he loved his family. But sumo was his grand passion.

Speaking of Kiyoshi-chan's family, there were six people in it, living in a small warm space no bigger than sixteen tatami mats. There were his father, his mother, Kiyoshi-chan himself, and his little sister Izumi-chan. But there were also his obaa-san and ojii-san, his grandmother and grandfather, who had lived forever in their own tiny two-mat room, bent in half and full of wrinkles.

Kiyoshi-chan never noticed the inside of his home, just because he had always lived there. It would have been harder to describe for him than his mother's face, just because he knew it so well. Someone else would have noticed the four tiny rooms, the dark beams and white plaster, the sliding paper doors, the genkan or entryway for shoes, the tatami, which was just right for sitting on, neither too hard nor too soft. Someone else would have smelled the particular smell of the place, which by now belonged to Kiyoshi-chan as much as his nose did, the smell of tatami and rice and fish and miso, all blended together in a way that would have seemed perfect to Kiyoshi-chan, if he had ever thought about it.

As with all Japanese homes, Kiyoshi-chan's began at the gate to its tiny yard. Inside and outside were equally part of the home, with only a low threshold and sliding doors to separate them. The outside part of Kiyoshi-chan's home was only the size of eight tatami mats, and was mostly covered with mouse-colored dirt that his mother swept free of footprints every day. It was enclosed by a high bamboo fence and thick shrubs that reached almost as high as the red roof tiles, which made their home as private and secret as a woodchuck's.

Since Kiyoshi-chan's yard was no bigger than a medium-sized room, it might seem to have been too small to have a garden. But in the corner of the yard was an arrangement of rocks and tiny trees that his father had set up, with great reverence. He had explained carefully to Kiyoshi-chan how he was trying to show the whole universe in this one little garden, and how each stone was a mountain, and the tiny stream of white pebbles a rushing river, and a waterfall. He had explained the difference between a crane-shaped stone and a turtle-shaped stone, and how the arrangement of stones told a special story from long ago.

Kiyoshi-chan heard this well, and tried to understand it, especially trying to take it as seriously as his father said it. How could the whole Universe fit into one little garden? Even his school was too big to hold in his mind all at once. And he knew that the Universe also included Wakamatsu-san's market, the train station, the vacant lot where he played baseball, and all of Kashiwa, Tokyo, Japan, and the whole world besides. Kiyoshi-chan's face wore a philosophical squint as he wrestled with this, making his father laugh. Kiyoshi-chan laughed, too, but there were actually moments when he felt a little sorry for his father for suggesting the whole idea. It was the first time he had ever caught his parents in anything like a mistake, and it made him melancho

ly for a day.

One Monday, after school, Kiyoshi-chan walked home the usual way, through a steady March rain. The school was two streets away, one of them loud and blaring with bicycles and little three-wheeled trucks. The next street was quieter, running between two cementblock walls, and Kiyoshi-chan kicked his way along through the puddles and the dusk, comfortable in his yellow raincoat and bright blue boots. He passed a tiny restaurant that was just a bright door in the wall, and saw through it two men sitting at the only table, eating noodles with chopsticks and talking loudly. The warmth and smell of food spilled out onto Kiyoshi-chan, making him think of his mother and supper, so he began to run, up the street, over the roadside gutter, through the gate, along the narrow covered pathway between the houses, and into his yard.

There in his yard were the light of home and the smell of food again, and rain falling all around. Something made him stop and stand still as a stone, hearing and smelling the rain with his whole self, the water streaming off his hat brim and around his face like a veil. He lifted his hands out to either side and let the rain beat on the yellow sleeves of his raincoat.

Then suddenly he noticed his father's garden.

It was different.

Kiyoshi-chan looked at it, perplexed. What was different about it?

He went over and squatted down on his heels, with his bottom only an inch from the streaming steppingstones. He looked hard at the garden. There were the usual shrubs and trees, the river and pool of pebbles carefully raked into ripples, moss growing in little mounds and over the stone lantern. Everything was there, in its place. The stones were dark with rain, and three ancient little trees dripped into the moss.

Kiyoshi-chan shuffled forward on his boots, inch by inch, and peered behind the lantern into the shadows of the tiny garden. In the dusk and rain, the shadows under the old dwarf pine trees seemed deeper than usual, as if they were hiding mysteries. Kiyoshi-chan thought he felt a small piney breeze blowing out from under them, down the pebbly waterfall, through the rocks of the miniature ravine, into his face. He felt a pang of gladness again, as he had when he had first come into the yard. For a moment he could almost imagine tiny deer moving among the trees, hawks the size of gnats soaring around the mountaintops. He leaned forward until his nose was almost touching the dripping pine needles, and closed his eyes, using his nose to hunt for another breath of piney mountain wind.

He had no idea how long he stayed there. His soul seemed to go out from him through his nose and wander through the wilderness of the garden, a tiny pilgrim with a staff and a great straw rain hat. The dusk had almost turned to complete darkness when his worried mother finally came out and discovered him.

"Kiyoshi-chan," she said, touching him on the shoulder. He jumped to his feet and shouted. His mother held him tightly, now truly alarmed. "Are you all right, Kiyoshi-chan? What is wrong?"

He was embarrassed. "Nothing, mama," he said, burying his face in her old familiar house kimono. "You startled me, that's all."

As he followed her inside, she laughed for only themselves to hear, to make him feel better. "When I first saw you there," she said, "I thought your father had added a new stone to the garden. A second crane-stone to keep the Old One company."

At the door, Kiyoshi-chan looked back one last time at his father's garden, and stopped with one foot already over the threshold and one still outside. He peered out into the dark. Did something move there behind the lantern, under the little pines? Did he see a quick glimmer of eyes? He thought of foxes, and bears, and demons, and was filled with fear. Stepping in quickly, he slid the door shut behind him.

CHAPTER 2

Night Sounds

Late that night, Kiyoshi-chan lay on his futon, wide-awake. Izumi-chan was asleep beside him, her face looking very white in the night, almost as if it were shining like a small moon. The rain was still running back and forth over the roof tiles, like ghostly children playing kickball, but it was not the rain that was keeping Kiyoshi-chan awake.

Kiyoshi-chan was remembering part of what had made him feel so happy earlier, when he had first returned home. He had been even gladder than usual ever since yesterday after school, when he had finally beaten the big twelve-year-old Taro-chan in the after-school sumo wrestling at the playground. Taro-chan was so big and strong that he usually beat Kiyoshi-chan with a ridiculous move, lifting the smaller boy up by the seat of his pants and setting him outside the ring like a baby. Then he would dust off his hands like a real sumo wrestler.

"For your information," Taro-chan would always say, "that was a lovely tsuridashi" He was proud to know the names of all the sumo techniques, from uwatenage to yorikiri. But a tsuridashi was to lift up an opponent by his belt, or mawashi, and to set him outside the ring. Everyone would laugh at Taro-chan's treatment of Kiyoshi-chan, knowing that they would soon have their turns to lose. Taro-chan was always the champion of the playground.

But yesterday Kiyoshi-chan had gone after Taro-chan like a fury, hooked his leg and pushed him over backward with all his might before the large boy had a chance to grab him. "Oof!" Taro-chan had grunted as he landed on his bottom, like a fat sack of rice. He sat there with a look of pure amazement on his face, his eyes as round as rice bowls.

Then Kiyoshi-chan had turned to the circle of astonished boys and carefully dusted his hands. "For your information," he said. "That was a lovely kawazugake."

Then everyone crowed at Kiyoshi-chan's great victory. Even Taro-chan got to his feet with a crooked smile and bowed with great dignity to Kiyoshi-chan, and Kiyoshi-chan grinned till his cheeks hurt.

Now tonight Kiyoshi-chan could not sleep for thinking about his victory over Taro-chan, and he laughed out loud again.

"Why are you laughing, Kiyoshi-chan?" asked his father from the other side of the paper doors. "Are you dreaming or awake?"

"I'm awake, papa," said Kiyoshi-chan. "I'm remembering Taro-chan yesterday."

He heard both his mother and father laugh in the other room.

"Go to sleep, Taiho," said his father.

"Skinny little yokozuna" said his mother.

So Kiyoshi-chan tried to go to sleep, but his mind was too wide awake to let his body drift away. He remembered how when the boys had finished praising him for his victory, the talk had turned to American baseball and the new season. They had talked about Bob Gibson, the great pitcher of the world champion St. Louis Cardinals, and about the amazing left fielder of the Boston Red Sox, whose name was too long and hard to pronounce. They just called him Yazu. Kiyoshi-chan loved baseball, but not as much as he loved sumo, and he wished they would talk of Taiho and Kashiwado and Sadanoyama instead, or even the wrestler Wakachichibu, who was as big as a mountain and who wobbled as he walked.

The night hours passed, the rain fell, and Kiyoshi-chan thought of many things while the whole house slept around him. Finally, in all the circling of his memories, he remembered the strange experience in his father's garden last evening. He tried to puzzle out what had been different about the garden, or if it were just the extra reflections of the rain that had made it seem depthless, as if his father's garden really was full of the Universe.

Then he heard the child crying.

At first he thought it was Izumi-chan making sounds in her sleep, so he turned to see what was wrong. But her face was still as round and white and silent as the moon, and she had a look as if she were dreaming pleasant dreams.

Then he thought it was a cat, and tried to close his eyes again to go to sleep. Their neighbors had a cat who sometimes came into their yard under the bamboo fence. It must be a very wet cat tonight, thought Kiyoshi-chan.

But then his eyes sprang open again. It didn't really sound at all like a cat when he listened closely. As he lay there and heard the strange sound go on, something brought back to him the thought of last night's garden and of its shadows, strangely fathomless and frightening. It was no child crying, he thought suddenly. It was a ghost or a demon, trying to lure him outside. He burrowed under his quilt,

his heart thumping in his ears.

But still it went on and on, like the saddest whimpering of a hurt beast, just loud enough now and then for him to hear it between the waves of rain. Kiyoshi-chan felt the sadness of it deep down in his stomach, and wanted to cry with it as if it were the voice of some universal sorrow. Silly person, he had to remind himself. He had no sorrow at all to speak of, and he had beaten Taro-chan with a lovely kawazugake yesterday. Why should he feel like crying?

Feeling brave, Kiyoshi-chan pushed back his quilt and stood up. He would go and see what the sound was, and he wouldn't wake his parents. He slid back the door of their room and padded in his bare feet around their futon. In the entryway he slipped on his father's great wooden geta, so his feet would stay out of the wet. Then he slid back the screen door and the wooden outer door, and stepped onto the outside platform. The rain poured off the roof like a curtain in front of his eyes. It was dark in the yard, but not as dark as he would have expected deep night to be.

He stepped forward to the edge of the platform and looked to the right, toward the gate and away from his father's garden. Somehow it seemed to him that if there was anything to see it would be in the garden, but he almost stepped back into the house without looking in that direction, as if he had done all he could do. He stopped himself with an exasperated exclamation, but still found himself reluctant to look where he knew he needed to.

"Remember Taro-chan!" he said aloud. He grinned at himself for doing it, but knew that in a world where such things happened, he could not step back now. With determination, he went right to the edge of the platform and peered through the dreary darkness into the shadows where his father's garden was. For a moment he could see nothing.

Little Yokozuna

Little Yokozuna